What are the members of Spatial Planning & Strategy up to? In this series of interviews we meet various members of the section and discuss their work, who they are, and have a look behind the scenes. Today, we meet Verena Balz and Marcin Dąbrowski, researchers in the TU Delft-led ‘DUST’ project: an extensive, multi-year programme created by a partnership of 13 academic and societal organisations in response to a Horizon Europe call for research on the future of democracy and civic participation. Verena is assistant professor at the section, principal investigator of the DUST project, and also has extensive professional experience as a senior urbanist. Marcin is assistant professor at the section too, and is the Research Leader of the section. During this interview, we delve into the DUST research programme. Where does the idea for DUST come from? What does the research programme consist of? And, what does DUST mean for spatial planning in the EU?

The Horizon Europe call for research on the future of democracy and civic participation (April 2022) was like hitting the jackpot. Verena recalls: “I saw this call two years before it was due, and I knew: this is where I want to go. For me, it was always a dream to use the regional design instruments that I study, also in my PhD, and to test them in a political science context.” Adding to this, Marcin says: “it is also really in line with the research agenda of our section. If you look at our long-term interest in regional design, in participation, in questions of spatial justice – all those elements are there. This was a great opportunity to bring them all together.” And so, Verena and Marcin co-started the DUST project. The total consortium of the project has grown to include thirteen partners in a wide variety of disciplines, including academic and societal partners; experts in economy, policy, political science, and spatial science; an architecture firm in charge of the art directorship, and a network partner connecting planning practitioners.

What is the DUST project?

“DUST stands for Democratizing jUst Sustainability Transitions,” explains Verena, “and in very brief: we are going to look how we can involve least engaged communities in multi-level place-based policy approaches to sustainability transitions. Now, this is just a bundle of key words,” she continues. “In more detail: we are looking into eight regions in Europe that have to step out of energy intensive industries, and we want to understand how we can involve communities who are most affected by this step in democratic decision-making.” Marcin explains the main problem: “regional scale participation is notoriously difficult, because of the distance to the citizens, and perhaps to the vagueness of this scale in relation to every-day life of citizens.” Verena: “I always want to underline this– DUST is not about participation on the local level, it’s all about taking these communities into this super complex multi-level decision-making world.”

Marcin outlines the structure of the project. “The beginning is quite classical. We combine quantitative and qualitative methods to explore the factors that are behind the limited engagement of different communities in place-based sustainability transition policies. And, we try to evaluate the performance of these policies in terms of enabling participation.” After building a theoretical foundation, DUST moves on to a case-study phase. “We have eight case studies to understand the diversity of context and understand how the context also shapes participation,” explains Marcin. “This case study phase is quite comprehensive,” adds Verena. She illustrates the depth of this phase: “for example, we have surveys investigating the perception of different communities and a media analysis where we investigate dominant climate change narratives at play in different regions. In Eastern Europe, such narratives can be quite decisive factors in participation.” Marcin continues: “Then, we narrow our focus on four case studies, where we will conduct experiments testing new participatory instruments.” As a last step, DUST will investigate wider applications. “Then we open up again, and think about ways in which we can upscale, in which we can disseminate this knowledge and tools to other places.”

A substantial component of the research focuses on policy and design tools. However, clarifies Verena: “our approach is that not one tool or instrument can fix the participation issue.” They strategize to bring together multiple digital and non-digital tools and precedents and build a format for upscaling participation from the local to the regional level and beyond. “One digital tool that we test is a tool that is tested very successful already in Taiwan: it’s an app for deliberation, not a yes-no voting app, but it’s an app where you can participate in formulating common statements. This is one example. Another precedent that we made part of our proposal is a format that was developed by UNESCO, called the Futures Literacy Lab approach. This is a format that helps people articulate their expectations and hopes in complex settings, and make them ‘future literate’. And then we have our own rich experience in using design in the context of governance and spatial planning.” DUST will investigate the upscaling from local tools to EU-wide policy. Verena: “We have very clear policy deliverables that aim at policymakers at EU level, we also have a transferability study as part of the proposal. So, some lessons will hopefully go across countries.”

DUST around Europe

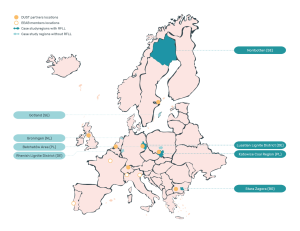

The project is truly multinational, focusing on eight different study regions in five EU-countries in the first phase, and four in the experimentation phase. The latter regions are the Katowice coal mining region in Poland, the Stara Zagora region in Bulgaria, Lusatia in Eastern Germany, and Norrbotten region in Northern Sweden. The four additional regions in the analytical phase are: Groningen (The Netherlands), the Rhenish Lignite district (Germany), Bełchatów around Łódź region (Poland), which is also a coal mining area, and Gotland (Sweden), shown in the image below. On the selection, Marcin explains: “the first criteria was: are these areas eligible for the Just Transition Fund – the European Union’s tool for supporting transitions away from energy-intensive industries in regions which are particularly vulnerable to such a shift?” He continues: “We looked also at the different national contexts: where is there already an ongoing debate on those processes? Within Poland, Katowice, for example, stood out as having already a lot of debate, very advanced on developing the regional plan for this transition. Also, this is where a lot of the tensions are.” The fact that there’s few southern or western regions is mostly due to budget constraints of the project. Marcin: “in an ideal situation we would like to cover all corners of Europe!” Verena explains: “We wanted to be able to study regions in depth. This is expressed in the fact that we have in every region a ‘societal partner’, who can link us to the communities in the regions. In Poland it’s a trade union organisation focusing on coal miners, in Lusatia it’s a competence centre for the participation of children and youth, and so on.”

The case study regions are designated as ‘structurally weak’. Verena explains the rationale for this designation: “the first reason is that they are undergoing these transitions, which means that large parts of the industries are going away. This looks very different in different regions. In some regions these energy-intensive industries are still fully there, which means we have regions where a large part of the population is still working here. That’s one aspect. And then there are different conditions per region. Norrbotten is extremely peripheral, for instance. You will also find differences in the history of these regions, more or less traumatic.” Marcin elaborates: “it’s a combination of factors. Vulnerability to transitions: how dependent these regions are on those industries. Also, the EU has its own classification of region with respect to development, which then guides the cohesion policy. Our regions are in ‘less developed’ or ‘transitioning’ regions.” Thus, each region has different conditions that makes it ‘structurally weak’. This is an important factor, he reflects: “We build on the assumption that context is really critical, for example in determining the degree to which those communities we want to study participate, and also for the implementation of policies. I think the recommendations we will produce will be place-specific and have to take into account those contextual factors to be effective.”

Reflecting on European Spatial Planning

DUST adds to a discussion on European Spatial Planning as well. Territorial cohesion is one of the goals of the European Union, but implementation of a territorial focus remains a difficult, unresolved issue. One reason is a matter of jurisdiction, explains Marcin. “It’s a bit paradoxical, because the EU is trying to put forward more place-based policies, trying to shape the territory, but it doesn’t have a planning competence – it’s a national competence. So, that’s where a mismatch happens.” Verena notes that there are different ideas about the role of ‘space, territory, and place’ in different disciplines. “As spatial planners, we are happy when we hear the EU say ‘we need a place-based approach’, , because we think: that’s us! But, in fact, a place-based approach can mean something totally different to an economist or regional policy maker. In these disciplines, there are concepts that we don’t fully understand. What is, for instance, ‘smart spatialisation’? When they speak of ‘territorial capital’, it is not a pretty built environment, it is jobs and innovation and industrial policy; it is different from what we mean in spatial planning.” There are thus many open questions, but Verena sees possibilities too: “there is a possible overlap – or cross-fertilization perhaps, between these understandings.”

With the project, this cross-fertilization takes concrete form. DUST focuses on concepts like active subsidiarity and place-based approaches, with this specific idea in mind. “These are relatively new concepts,” details Marcin, “so we are trying to also develop them, by testing how they would actually work out, and test how we can support this implementation with different tools.” Verena: “For me, this is the most interesting part. For example, the place-based approach says: you need to involve local actors, because they know the place. How do you do that? What kind of knowledge is useful to extract from the local level and put into this decision-making process?” “Active subsidiarity, too,” says Marcin, “is quite new. Subsidiarity is now interpreted as something for the authorities at different levels who are engaged in decision-making and implementation of multi-level policies, but we go a step further, because we say: it should also be done with the citizens.”

“One could argue,” he concludes, “that through the territorial lens, actually a lot of issues and policy agendas meet. And it is also an interesting entry point to ensure participation and engagement and develop legitimacy of the policies to steer sustainability transitions. This is where change is visible if you can produce spatial change, and relate those big policy agendas to change on the ground.”

More information

The DUST website is now live! Check https://www.dustproject.eu/ for more news, information, and contact details.

If you are interested in following the project on social media, you can find DUST on Twitter, Instagram, and Facebook using @dustproject.

DUST is also on LinkedIn: https://www.linkedin.com/company/dust-democratising-just-sustainability-transitions/.